By Bich Ha Ngo

“It’s fun and because it’s healthy too. And that’s something you do on your own and one can see how it grows. And that is a pleasure when you look at it and it grows and blooms and then you can harvest it.” (Anonymous)

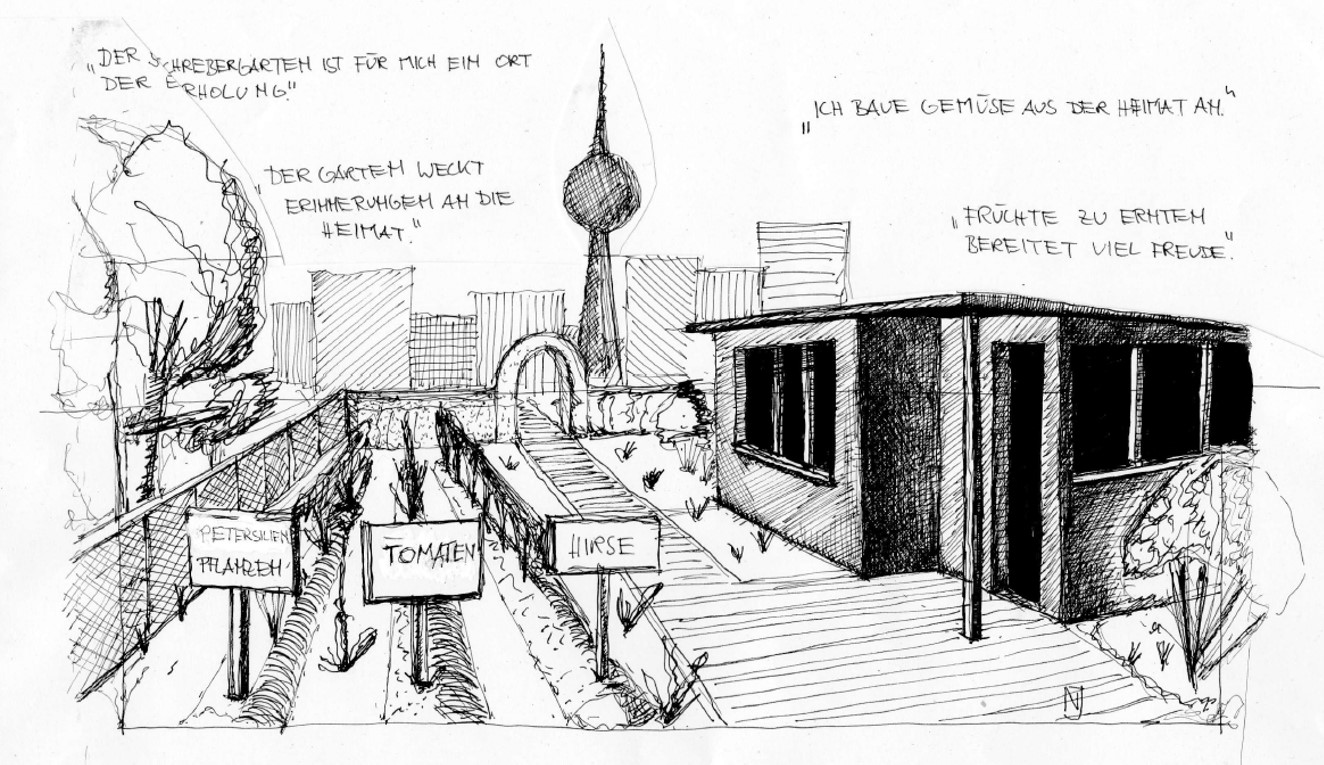

The above quote was part of a conversation which I held in the context of my study project at the HU Berlin at the Division of Gender and Globalization. It reflects the joy of subsistence cultivation of self-grown food in an allotment garden. While new digital food supply platforms are emerging, such as bio-boxes or other delivery services, allotment gardens are still ‘analogue’ places of food provisioning. The starting point of my study was the research project PLATEFORMS which deals precisely with this diversity of food provisioning platforms and examines how food practices in households are influenced by the mentioned socio-technical innovations. What potentials and challenges arise in households? In my study project, I was primarily interested in examining the relation between food and migration in Berlin. Since there is hardly any literature on this topic, especially from German-speaking, I decided to investigate the field exploratory. Thus I approached the still largely unexplored field of research with little preconception and generated my knowledge and analysis from the interviews themselves.

Why am I specifically interested in this connection and how does it go together?

In the course of history, Berlin, as the capital of Germany, has developed into a cosmopolitan melting pot where a large number of people with a migration biography live. Food consumption as a daily practice structures the everyday life of all people. In the course of the migration to Germany respectively Berlin, food practices also became a way to preserve memories of the home for many people. The various supermarkets with Asian and African products have become indispensable from Berlin and can be seen as a reflection of the demand of the respective residents. It is a particularly important concern for me to explore the link between migration and food, as the dimension is essential in respect of migration. Besides it has received very little attention in previous research. In order to examine this significant part of the everyday life of people with migration biographies, I concentrated in my research on individual food production in urban areas. Thus my interest in the food cultivation in Berlin’s allotment gardens.

An allotment is a defined as a piece of land, which, along with many other allotments, is considered part of a small garden or garden colony. With an amount of 67.000 parcels out of 91.000 in total in Germany, Berlin hosts the biggest amount of parcels within Germany (Bundesverband Deutscher Gartenfreunde, 2018, Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Development). Within my research project, I considered the allotment garden as a small, socio-cultural place of recreation and food cultivation. It plays a historically significant role within the German context and offers residents in urban space an individual natural space.

As part of my research, I had the opportunity to talk to two people of the first and second generation from Turkey and a person of the first generation from Italy. My interest was primarily to explore what the cultivation of food in their garden means for their everyday life. Striking in the discussions were the overlapping topics of all persons. For all three people interviewed the garden was not just a place of recreation: all three emphasized the relevance of growing their own fruits and vegetables from their home country.

“But mostly when we are in Turkey, we bring that with us. Beans or other things. I also brought fruits from Turkey. I brought my apricots from Turkey and these plums there. This is also from Turkey, but someone else brought it along and I have grapes here. This is again from my area of the Black Sea. It also reminds me of my childhood and it also has a different taste.” (Anonymous)

Thus this emphasis on the cultivation of brought varieties stems from the desire to maintain childhood memories and memories of the homeland. Furthermore, respondents described their garden as a place of reproduction, a place where they can not only recover from urban life, but also produce their own food, thus creating their own ‘food platform’. Especially two people strongly emphasized to exclusively grow organic products. Moreover, the sharing of leftover produce turned out to be a relevant topic in their food production.

“If we have visitors here, even from the closer relatives. Of course they can take everything. That is more kind of a sharing, taking and giving.” (Anonymous)

Another person similarly described sharing her produce with other people from the Turkish community inside the allotment garden. Sharing with the German community though has so far seemed a difficult obstacle.

All in all, the project has demonstrated the need for further research on this matter from a migrant perspective. This would not only advance the discourse on food provisioning, it would moreover include and reveal marginalized perspectives that so far are barely heard. The research has also illustrated that individual perspectives on food consumption and production are representing a part of one’s own identity and therefore are strongly influenced by one’s own biography. Finally, it is important to emphasize that the gardens have a positive effect on many levels and can be understood as platforms, because they go beyond self-consumption by sharing the harvest with others. It could be demonstrated that the ‘analogue food provisioning platform’ allotments offers respondents the possibility to feed themselves more self-determined and more diverse; above all because the respondents themselves can create supply structures that the ‘common’ platforms do not offer them.

The project was supervised by Meike Brückner and Suse Brettin within the project seminar “Qualitative and participative methods of field research”.